(Please consider making a contribution to Welcome to Pottersville2 or sending a link to your friends if you think the subjects discussed here are worth publicizing. Thank you for your support. I really appreciate it. Any contribution will make a huge difference in this blog's ability to survive.)

Yay.

Looks like Nate Silver had made it official before the voting even gets going on Election Day.

So, no worries about that touted change from progressive government and Supreme Court monsters (more monsters - new monsters!).

Nate Silver: Obama’s Chance of Winning Now at 91.4%

If Silver’s right, Obama is headed for an electoral landslide

Charles Johnson

Nov 5, 2012 at 8:48 pm PST

Tonight Nate Silver’s polling models are giving President Obama a 91.4% chance of winning, with 314 electoral votes compared to Mitt Romney’s 223.

On the other hand, if you aren't that impressed with all those great progressive rulings from the current center right Supreme Court . . .

. . . confirming far-right corporatist nominees; in the White House, Democratic presidents nominate their own corporatists, who in turn conveniently manage just enough support from Senate Republicans. Thus do the two corporate-financed parties cynically connive to push the “center” of American politics—in all three branches of government—ever farther to the right—so far to the right that the imposition of onerous economic servitude for millions of Americans in the form of Obamacare is widely hailed as a victory for sound “progressive” governance, along with other lavish corporate benefactions such as the bailouts of the Wall Street fraudsters, the export of hundreds of thousands of jobs through a succession of bipartisan “free trade” agreements, and the pampering of the oil- and coal-extraction industries whose unchecked power threatens the planet with climate apocalypse._ _ _ _ _ _ _

Clearly, then, the basic political direction of the Supreme Court does not hinge on the whether a Democrat or Republican occupies the White House; in either case we can expect enhanced power and wealth for the 1 percent and growing suffering for the rest of us. Fortunately, given the proven ability of mass movements and political/social pressures to stymie the rapacity of the elite, the future of the country need not be served up to the not-so-tender mercies of the corporate law firm known as the Supreme Court. But as long as the citizenry heeds the liberal zombies and passively consigns its fate to those nine lawyers—rather than taking history into its own hands by organizing and fighting for its civil and economic rights—the Justices will gladly welcome our cooperation.

Unless the quadrennial march of the Supreme Court zombies awakens into a perennial march of an enraged and aroused populace, we are headed for a self-fulfilling political prophecy: a corporate-dominated Night of the Living Dead.

William Kaufman is an educational writer who lives in New York City. He can be reached at kman484@earthlink.net.

The story you're sometimes told about the sub-prime bubble is that it was a bunch of people who should never have been lent a dime suddenly being given the keys to the palace of debt. Wherever that applies, it isn't Weston Ranch. As Voge points out, household incomes here average between $60,000 and $80,000 a year: enough to warrant a middle class lifestyle, but insufficient to afford one in the pricey Bay Area. So, just as Susan's father did, they moved further and further out.

"At 4am, you'd see the house lights come on," is how another Weston Ranch resident, Alicia Calhoun, remembers life during the supposed good times. "By 6am – click! — the garage doors would go up and the street would empty out." Calhoun worked in customer services for a bank in Palo Alto: at least a four-hour round trip, on top of the 9-5 job and looking after her kids.

That commute, those dodgy mortgages, this entire "bedroom community" deep in the Central Valley: all were products of a country growing vastly more unequal within a generation.

According to IMF researchers Michael Kumhof and Romain Rancière,

by 2007 the richest 5% of Americans were pocketing 34 cents of every dollar earned in the US; a level of inequality last seen just before the Wall Street Crash of 1929. Most of the rest of the country saw negligible rises in their wages, and had to rely instead on borrowing. What followed was the crash of 2008 – and human and civic wreckage in places such as Stockton.

In T-shirt and shorts, Susan's mood flits between volcanic and eve-of-holiday. "You know how many homes here have been foreclosed? That one. That one. That one." She's jabbed her finger along almost the entire cul-de-sac. "Only the family next door haven't. I give them six months."

Weston Ranch, which is about 80% non-white, is basically Obamaville: full of the middle-class families he claims as his bedrock. But throughout the sub-prime freefall, his administration in effect delegated responsibility to local governments and market forces. And even in the last days of this campaign, neither Obama nor Mitt Romney has seriously addressed the housing crash. Yet according to the Chicago economist, Amir Sufi, the property bust and the recession have between them wiped out the 20 years' worth of savings by middle-income and poor families.

Susan's brother Dusty has been helping shift boxes. Another jabbing finger: "He fought in Iraq and now he's back here and the only jobs around are in warehouses at $9 an hour." Breath. "This economy is garbage."

Stockton is a metaphor for the US.

Don't ignore the lessons found in this morality tale.

Stockton, California: 'This Economy Is Garbage'

The middle-class families Obama claims as his bedrock are suffering in a city where foreclosure and violence are rampant

2 November 2012

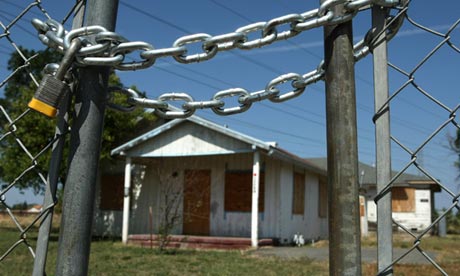

An abandoned home behind a padlocked gate in Stockton, California. The city became known as the foreclosure capital of the US. (Photograph: Justin Sullivan/Getty Images)

In some towns, visitors are warned to keep an eye on their stuff, or to watch out late at night. In the Californian city of Stockton, the anxiety is more precise – and it kicks in early. "Take care downtown after 5pm," one local person told me. "Don't hang out too long."

A few hours later, I saw what she meant. Almost as soon as the offices shut, the city centre empties. Then the sun goes down and a different cast takes to the streets: the homeless, the drug dealers, and clusters of young men patrolling up and down on bicycles.

Stockton ranks among America's 10 most dangerous cities, and everyone here seems to operate under a self-imposed curfew. The commuter admits she doesn't dare go to the cinema after 8pm; the father expects his 18-year-old daughter home by 10 – "and she totally gets why." Others prefer not to go out at all. All give the same reason: the spiralling number of violent crimes.

Last weekend, the city notched up its 60th murder of the year, up from 24 for all of 2008. At just under 300,000 residents, this river port has about the same population as a London borough. Imagine a couple of your neighbours getting killed every week, and you'll understand why almost all the conversations here touch on a recent homicide.

It happened in this park, they tell you; outside that drive-through; on a first date. Then the inevitable coda: "It happened in broad daylight."

The last time Stockton attracted so much attention was in 2008, as the biggest housing bubble America had ever enjoyed was turning into the biggest bust it had ever suffered.

With nearly one in 10 homes repossessed that year alone, the city became known as the foreclosure capital of the US and formed part of the backdrop of economic catastrophe against which Barack Obama was elected president.

Then: nothing. For the next four years, the name barely cropped up in the news, so that you'd have been forgiven for believing the bad times had eased off. Until this summer, that is, when it became the largest city in America to file for bankruptcy. The bushfire had not died down, far from it – while the rest of the world was not looking, it had escalated.

The two-and-a-half-hour drive there inland from San Francisco moves from coastal grooviness to municipal crack-up. You're told as much by the local TV news network, whose reports bear the strapline Stockton in Crisis. Or you can infer it from the defensiveness of the signage. "Stockton is Magnificent!" reads one banner. "Don't give up!!!" says the hoarding over empty shop fronts.

Apart from the odd grocery store and a giant wig emporium, what downtown Stockton has in abundance is abandoned shops.

What makes the dereliction disconcerting is that it nestles amid civic grandeur, some of it quite recent. Stockton rivalled Seattle and San Francisco for importance as a transport hub during the gold rush on the 19th-century west coast, which must help to account for its grand boulevards, spacious enough to march elephants.

But there are also marbled bank offices, refurbished theatres and government offices, none of which look more than a few years old.

"The downtown could have been like Paris's 6th arrondissement!" local property developer Dan Cort tells me. While it sounds preposterous now, his claim underscores one thing: there can't be many cities in America unravelling as fast as this one.

Yet it would be wrong to dismiss Stockton as a curio, an outlandish disaster that couldn't happen here, for three reasons. First, many other towns in California, a state of 40 million that on its own would count among the 10 biggest economies on earth, are scrambling to avoid bankruptcy. This tale shares elements of the debacles in Greece, Spain and Britain, too – almost as if all the factors behind the western meltdown had been chucked in a Walmart blender and poured over one small town.

What's unfurling here sums up the distinctive, dangerous way in which the great slump is playing out. Extreme it may be, but Stockton's story is also one version of a future that awaits many other cities, including those in Britain.

Let's begin with that last point. Most recessions follow a familiar waltz. First, there is the economic downturn, then there are the politicians' responses, before the social fallout: cause, effect, aftermath. But Stocktonians don't talk about a recession; they call it a depression. With one in eight workers out of a job, unemployment is almost double the national average. Six years after the peak of the market, house prices are still around half what they once were.

The local council's cash used to come from property and sales taxes; when those dried up, it rammed through cuts: the police force was shrunk by 25%, the fire department slashed by 30%, libraries and community centres either closed or are on short hours. Finally, this summer, officials ran out of services to shut, and declared the city bust.

As has happened in southern Europe, and threatens to happen under David Cameron too, this slump has been so severe and so prolonged that the economic, political and social crises are now overlapping, and amplifying each other.

To see that play out, head to Weston Ranch, a southern suburb devastated by the sub-prime mortgage crisis. According to research by Maianna Voge at George Washington University, almost one in three houses on some blocks suffered foreclosure in the bust.

When a Guardian reporter last dropped by, in 2008, he noted a forest of estate agents' boards and window signs: "Bank-owned – no trespassing". Four years on, there's much less of either. Buyers have since come along – but, rather than the families of old, they're often speculators, holding out for a blip in the market before offloading their auction bargains. While waiting, they rent the properties out carelessly and cheaply. Among these Frank Capra-esque homes, the signs of distress are now more subtle: cracked windows and lawns with overgrown brown grass.

On this afternoon, the only activity is on one driveway with a removals van. Sure enough, the bank is foreclosing on Susan and her family in the morning. Within a few minutes it all comes out: how her father moved them all here from Fremont in San Francisco's Bay Area; how his ultra-low "teaser rate" mortgage repayments rocketed without warning. How, just as that happened, property prices plunged so that they were "upside down", with the house worth less than they'd paid for it. How the lender didn't return their calls. How her father was diagnosed with cancer. Finally: how he'd died at the start of this month, just as the new buyer, one of the investors taking over the area, had offered her $3,000 to return the keys and leave without smashing the place up.

The story you're sometimes told about the sub-prime bubble is that it was a bunch of people who should never have been lent a dime suddenly being given the keys to the palace of debt. Wherever that applies, it isn't Weston Ranch. As Voge points out, household incomes here average between $60,000 and $80,000 a year: enough to warrant a middle class lifestyle, but insufficient to afford one in the pricey Bay Area. So, just as Susan's father did, they moved further and further out.

"At 4am, you'd see the house lights come on," is how another Weston Ranch resident, Alicia Calhoun, remembers life during the supposed good times. "By 6am – click! — the garage doors would go up and the street would empty out." Calhoun worked in customer services for a bank in Palo Alto: at least a four-hour round trip, on top of the 9-5 job and looking after her kids.

That commute, those dodgy mortgages, this entire "bedroom community" deep in the Central Valley: all were products of a country growing vastly more unequal within a generation. According to IMF researchers Michael Kumhof and Romain Rancière, by 2007 the richest 5% of Americans were pocketing 34 cents of every dollar earned in the US; a level of inequality last seen just before the Wall Street Crash of 1929. Most of the rest of the country saw negligible rises in their wages, and had to rely instead on borrowing. What followed was the crash of 2008 – and human and civic wreckage in places such as Stockton.

In T-shirt and shorts, Susan's mood flits between volcanic and eve-of-holiday. "You know how many homes here have been foreclosed? That one. That one. That one." She's jabbed her finger along almost the entire cul-de-sac. "Only the family next door haven't. I give them six months."

Weston Ranch, which is about 80% non-white, is basically Obamaville: full of the middle-class families he claims as his bedrock. But throughout the sub-prime freefall, his administration in effect delegated responsibility to local governments and market forces. And even in the last days of this campaign, neither Obama nor Mitt Romney has seriously addressed the housing crash. Yet according to the Chicago economist, Amir Sufi, the property bust and the recession have between them wiped out the 20 years' worth of savings by middle-income and poor families.

Susan's brother Dusty has been helping shift boxes. Another jabbing finger: "He fought in Iraq and now he's back here and the only jobs around are in warehouses at $9 an hour." Breath. "This economy is garbage."

The rec where Susan used to stroll has got so violent it's been dubbed Bullet Park. And last summer, she says, about 60 teenagers got into a pitched battle on the grass in front of her house. "They were going at each other with metal poles." Her husband phoned the police again and again, but they were too short-staffed to help. "It went on for hours."

When I run this story by police sergeant Kathryn Nance, she is puzzled: "We would have come out for an incident like that." Yet as we sit in her patrol car, she taps at the laptop: 6.30 on a Friday evening and there are already 27 outstanding calls for assistance. Top of the list is a rape reported an hour and a half ago, yet which no officer is free to deal with.

Nance's officers pile into a run-down area to chase some warrants. It's a sweep that the accompanying local TV reporter seems ecstatic about filming, but which feels like a formulaic show of police strength; strength that the downsized force no longer has. A colleague, Mark, estimates there are promising leads on more than a dozen murder cases but no manpower to investigate them. Nance talks about how the cuts made by various council departments are making parts of Stockton into no-go areas. She drives past one block and sighs: "There used to be parks and it was cleaned up. In the past four years it's gone bad again: dope dealers and vagrants.". And hassling drug dealers has become an occasional pursuit

If you don't want your area to go bad, you have to lay on your own services. On the "miracle mile", the boutiques spend their former marketing budget on a security patrol and street sweepers. They even maintain municipal car parks. A local hotelier pays to keep two public swimming pools open.

Such a sudden, drastic downgrade in what Stocktonians can expect from their mortgage lender, their council, their police, their neighbours, not to mention their own homes and pensions is dizzying even for the well-off.

As a developer of affordable housing, Carol Ornelas patiently talks me through what the sub-prime crisis means for her customers. Then she mentions her own situation – and the rush of words is like letting the air out of a balloon: "I used to live in middle-class America; now I don't know where I live. What I've seen come into my neighbourhood after all the foreclosures ... I don't even want to be around it." Again, she talks of fights in the yard just opposite.

Yet a quarter of an hour's drive from Nance's block-gone-bad is Brookside: an empty six-lane highway, a country club, and a string of small gated communities bearing such names as Nostalgia, where houses back on to fake lakes. Sneak inside and you see marble statues of cherubs. One cliché about recessions is that they make rich and poor slightly more equal. Not this time: according to Berkeley economist Emmanuel Saez, the top 1% saw their incomes soar by 11.6% in 2010; the wages of the other 99% grew only 0.2%.

"The American dream used to be within reach of the middle class," says Ornelas. "Now it's on offer only to an elite."

Stockton's city hall bears an inscription: "Let that which the fathers have builded inspire their sons to civic patriotism." Inside, the mayor's office is full of photos of what the city fathers have built in the past decade: a baseball stadium, an arena (where Neil Diamond played to a half-empty auditorium for a million-dollar fee), a swanky hotel – all around a redeveloped waterfront. They're the kind of job-free cultural makeover projects that middle-aged officials threw up all over the west in the noughties. In Stockton, estimates Jeffrey Michael at the local University of the Pacific, they were largely paid for by $100m in bonds issued over three years. For Ann Johnston, who only took over as mayor after the building spree: "Paying for these things is why we're now bust."

Well, yes and no; Stockton's problems go much deeper. Spend even a little time here and you notice something missing: middle-income employment. To the south are low-wage warehouses and food-processing plants, but the local public sector is the only home for anyone who wants a middle-class job without having to drive two hours. The city's regeneration and its encouragement of new housing estates was an attempt to bring in middle class people while skirting over the lack of decent private-sector employment. "They wanted a white-tablecloth kind of town," says former planning official Denise Jefferson.

The most grotesque example of that was a restaurant. Paragary's does a roaring business in the state capital of Sacramento, selling hand-cut rosemary noodles with seared chicken to people with large expense accounts. The city paid $2.7m in redevelopment funds to build a branch of Paragary's: its valet parking and expensive menu drew more resentment than custom, and it closed down within months.

In some ways, the entire debacle was no different from what much of Britain tried under New Labour. Except that, since Californian cities depend on property and retail taxes, Stockton council had a vested interest in inflating its bubble – only then could it keep paying for services and infrastructure to the new housing estates. As former city manager Dwayne Milnes says, "The entire system was a Ponzi scheme."

The result is a glut of houses and a glut of debt, both of which will take a long time to sort out. It's hard to imagine a time when the builders' cranes will start up again. The downtown developer Dan Cort tells me about a rival who recently pulled plans to build new houses on land by the motorway. "He's made it a walnut orchard instead." En route to the airport, the University of California sociologist Jesus Hernandez and I stop off and there they are: instead of rows of suburban homes, lines of walnut trees. Far away is the belch of Central Valley traffic; close up is the hiss of sprinklers.

As we set off, I mumble something sentimental about Stockton's retreat from postmodern financial engineering back to its agricultural roots. Jesus corrects me: "He's probably passing it off as farmland and getting a great tax break."

And what should we be doing?

Ain't gonna happen.

Ask the toxic Mittens crowd.

As we watch developments in New York and New Jersey on the heels of Hurricane Sandy, it is instructive to compare another cleanup 15 years ago in North Dakota after another natural disaster, the flooding of the Red River and the fire in downtown Grand Forks.

Meanwhile in Washington State, the Treasurer resists a public bank because of the "risk" involved, as if the Wall Street banks are trustworthy partners! "Funding is different for BND from that of other commercial banks," says Standard & Poors (see below). Because it is different, it's past time to put public money into public banks -- for the public good, as the Bank of North Dakota so clearly demonstrates during times of prosperity -- and times of natural disasters.

Public Banking to the Rescue

How BND Saved Grand Forks in 1997

Written by Jim Morrow and Ira Dember, PBI Volunteers

Folks in Grand Forks, North Dakota will never forget April 1997, when record flooding of the Red River and major fires devastated the city. They also won't forget that it was Bank of North Dakota--the nation's only bank owned by a state--that put people above profits. The BND rushed to the rescue with financial flexibility and generosity of spirit in the public interest that no privately owned bank could match.

From this valley they say you are leaving.

We will miss your bright eyes and sweet smile,

For they say you are taking the sunshine

That has brightened our pathway a while.

Unlike the cowboy's lament, for Grand Forks, sunshine was part of the problem. Most years, the region's winter snows melt gradually over a span of months. But by mid-March, temperatures had hovered below 40 degrees for four months straight. Ten feet of undiminished accumulated snow pack loomed in the Red River watershed. Beginning March 18th, temperatures suddenly warmed above freezing and remained high for 27 days straight. Runoff from snowmelt swelled the Red River and its tributaries into torrents.

So come sit by my side if you love me.

Do not hasten to bid me adieu.

Just remember the Red River Valley,

And the cowboy that loves you so true.

The National Weather Service predicted the river would crest at 49 feet, equal to the area's highest previous flood level in modern history. Sandbag dikes, built to handle a flood at that level, protected the town - until they didn't. On April 16 the Red River surged to 49 feet and, in subsequent days, kept rising: 50, 52, 54 feet. On April 18, floodwaters breached a dike, then others.2 All hell broke loose.

Mayor Pat Owens ordered 50,000 people to evacuate3-at the time the largest US evacuation since Sherman's burning of Atlanta, 133 years earlier. But Grand Forks' troubles had only begun. In a turn of events that would make Murphy blush, floodwaters shorted electrical equipment in a downtown building. National news media carried dramatic pictures of firefighters struggling to fight blazes in buildings surrounded by water. Fire spread to apartments where 40 stalwarts had defied Mayor Owens' evacuation order. Emergency workers had to rescue them from both fire and flood before firefighting began. The inferno consumed 11 buildings, 60 apartments, and the Grand Forks Herald, with its 120-year archive.4

The Toll

Incredibly, not a single person in Grand Forks died as a result of these twin disasters. But the town and its sister city, East Grand Forks on the Minnesota side of the river, lay in ruins. Floodwaters covered virtually the entire city and took weeks to fully recede.5 Property losses topped $3.5 billion.6

The flood inundated 16 of 22 local schools, 315 business and a staggering 75% of area homes. In all more than 5,000 businesses were affected by an earlier blizzard plus the flood and fire. Some businesses sustained only minor damage; others were totally destroyed.7

Enter BND - North Dakota's Public Bank

Soon after floodwaters swept through Grand Forks, the state-owned Bank of North Dakota began taking unprecedented action to help families and businesses recover. Led by BND's then-president and CEO John Hoeven--future North Dakota governor and US senator--the bank quickly established nearly $70 million in credit lines:8

· $15 million for the ND Division of Emergency Management

· $10 million for the ND National Guard

· $25 million for the City of Grand Forks

· $12 million for the University of North Dakota, located in Grand Forks

· $7 million allocated to raise the height of a dike at Devil's Lake, about 90 miles west of Grand Forks

BND also launched a Grand Forks disaster relief loan program and allocated $5 million to help other areas affected by the spring floods. With BND leading the way, local financial institutions matched these funds, making available more than $70 million altogether.9

Flooding swept away many jobs, leaving families without a livelihood. BND coordinated with the US Department of Education to ensure forbearance on student loans. The bank also worked closely with the Federal Housing Administration and Veterans Administration to gain forbearance on federally backed home loans and to establish a center where people could apply for federal/state housing assistance. Further, BND worked with the North Dakota Community Foundation to coordinate a disaster relief fund, and the bank served as the fund's deposit base.10

BND didn't stop there. Agriculture has long been a North Dakota economic mainstay. In the Great Depression, BND helped keep families on their farms.11 With the record 1997 spring floods, many farm families again faced financial ruin. BND responded by reducing interest rates on existing Family Farm and Farm Operating programs. Families used these low-interest loans to restructure debt and cover operating losses caused by wet conditions in their fields.12

To help finance the disaster recovery, BND obtained funds at reduced rates from the Federal Home Loan Bank, in turn enabling the publicly-owned bank to pass along cost savings to flood-affected borrowers in the form of lower interest rates.13

Some impacts can be readily measured; others may be deduced. Between the 1997 floods and 2000, Grand Forks lost 3% of its population. Sister city East Grand Forks, right across the river in Minnesota, lost 17% of its population in the same period.14 Coincidence? Or did Grand Forks--one minute away by car--achieve a more rapid, more graceful economic recovery, in part because of what North Dakota's unique, publicly-owned bank accomplished there? Likely, one could also compare the results of BND's efforts to what happened in New Orleans, after hurricane Katrina, and end up with the same answers.

Conclusion: Unparalleled Advantage

In 1997 the people, businesses and institutions of Grand Forks, North Dakota experienced firsthand the unparalleled ability of a publicly-owned bank to place the public interest above all other considerations. Because BND has no shareholders other than the State of North Dakota, it has far-reaching flexibility and, in emergencies like the 1997 flood, can act quickly to catalyze and coordinate resources ranging from federal agencies to local community banks.

No other institution in the wake of 1997's overwhelming disaster combined the credibility, clout, capital, and connections to protect the public interest as BND did for North Dakota families and small businesses.

The same holds true today. People and businesses across America are drowning in unsustainable debt. They face a flood of foreclosures, many with home values that are "underwater." Meanwhile conventional banks keep credit tight, drying up the very resource that businesses need to hire more people and get the economy moving again.

If each state had its own public banking institution, today's drastic situation might be very different.

Just ask anyone in Grand Forks who lived through 1997.

Originally published on PBI website. See link for footnotes.

_________________________

For nerds (not) only:

BND's Loan to Core Deposit Ratio - the Key to its Success

Discussion of BND Risk and loan-to-core-deposit ratio

Standard & Poors discusses the loan-to-core-deposit ratio for BND in last December's Research Update (see page 4):

http://banknd.nd.gov/financials_and_compliance/ pdfs/SP_BankofNorthDakota_ December2011.pdf

The bank's funding is "average" and its liquidity is "adequate," in our opinion. Funding is different for BND from that of other commercial banks. By state law, all state funds and funds of state institutions are deposited with BND. None of those deposits are federally insured, but they are guaranteed by the state. Noncore deposits provide the majority of BND's funding, while core deposits constitute roughly 26% of its funding base. Because core deposits do not fully fund the loan portfolio, the loan-to-deposit ratio is high at 259%. Noncore deposits primarily consist of large certificates of deposit from local state agencies, which the law requires them to deposit at BND. When those state-sourced captive deposits are added to the core deposits, the loan-to-deposit ratio improves to 74%. We recognize the stickiness of these deposits. The bank also has access to additional funding from the Federal Home Loan Bank of Des Moines, and it can borrow from the Federal Reserve discount window. The bank can also enter into a repurchase agreement using the securities in its $584 million available-for-sale investment portfolio as collateral.

More Weekend Reading:

Fundamentals re. debt-based privatized money:

Introductory videos and other educational resources.

http://www.positivemoney.org.uk/videos/

Fundamentals of public banking:

Material on public banking throughout the world, including studies in the USA.

http://www.publicbankinginstitute.org/ public-banking-research.htm

Information on Bank of North Dakota (BND) Loan Programs:

http://banknd.nd.gov/lending_services/index.html

Information on BND Returns, Credit Rating, and all Annual Reports:

http://banknd.nd.gov/financials_and_compliance/ annual_reports.html

No comments:

Post a Comment