This is going out a little bit late, but you know how events are really picking up speed now and it's tough to get everything in.

Too bad there's no real investigative reporting going on for these affairs. Or is there? (See below.)

Credit Suisse 'Cloak-and-Dagger' Tactics Cost US Taxpayers Billions – Senators John McCain and Carl Levin

(EXTRA! The White House Has Been Covering Up the Presidency's Role in Torture for Years

By Marcy Wheeler, The Intercept

14 March 14)

I dare you to read this entire essay and still believe that there is any federal law enforcement of banking in the USA! USA. usa. Or in Great Britain.

There is one huge difference between what Picard entered into the public court record and what the U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of New York, Preet Bharara, entered into the public record yesterday: Picard named names – at JPMorgan and at the feeder funds that blindly shoveled billions to Madoff. All of that explosive naming detail is missing in Bharara’s neat settlement, suggesting that is how the U.S. Attorney’s office wrung such an expensive settlement out of JPMorgan in exchange for no prosecutions of individuals and a deferred prosecution agreement against JPMorgan itself.

JPMorgan will pay $1.7 billion to the U.S. Justice Department to compensate victims of the fraud. It will pay another $543 million to Picard’s trustee fund to compensate victims; and it will pay a $350 million fine to the regulator of national banks, the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency.

We’ve been researching and writing on the Madoff fraud since the news first broke in December 2008. Below we present some of the critical pieces of the puzzle explaining how Madoff perpetrated the scheme for so long with the willful blindness of so many.

So, I was thinking about how this whole scenario works now.

When George W. Bush and Chin Chin Cheney were in charge, it must have been a much more obvious (due to Cheney's well-known penchant for always having to be in-the-know and at the top of every venomous pyramid) and involved scenario enriching everyone up and down the scam scheme. Thus, how long it went on and why no one ever outed Madoff (to protect their own skins against really lethal creatures).

Today, it's hard to see President "I'm Doing the Best That I Can With Assholes Who Won't Do Anything Even a Tiny Bit Positive for the Country" actually partaking of the conspiracy aspect of the plot, but someone at the top of the power heap must be as the settlement would not have been so "generous."

Wall Street On Parade has done the honors of reporting on this for us extended into every possible avenue, including an almost banal murder mystery (along with a few articles from the Wall Street Journal, that must only exist because they contain anger towards the players who've left them out of the take).

Bombshell Documents Vanish in the JPMorgan-Madoff Investigation

By Pam Martens: February 25, 2014

According to a Freedom of Information Act response received by Wall Street On Parade, Federal law enforcement may share the blame with JPMorgan Chase for allowing Bernard Madoff’s Ponzi scheme to be perpetuated for so long.

Jennifer Shasky Calvery, Director of FinCEN, Speaking at a Press Conference to Announce Federal Charges Against JPMorgan for its Role in the Madoff Ponzi Scheme

On January 7 of this year in a press conference called to announce felony charges against JPMorgan Chase for its role in the Madoff Ponzi scheme, U.S. Attorney Preet Bharara, FBI Assistant Director-in-Charge George Venizelos, and the Director of the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network, Jennifer Shasky Calvery, took turns at the podium excoriating JPMorgan for observing brazen, long-term money laundering activity occurring under its nose in the business bank account it held for Bernard Madoff while ignoring its legally mandated duty to file a Suspicious Activity Report (SAR) with the federal government.

The Financial Crimes Enforcement Network, known throughout Wall Street and the banking world as FinCEN, is a bureau of the U.S. Treasury Department that receives the SARs and is tasked with making sure the reports are seriously investigated.

JPMorgan Chase and its predecessor banks, Chase Manhattan and Chemical, oversaw Madoff’s primary business account for more than 20 years. During that time, flagrant money laundering signs should have set off automated bells, whistles and sirens inside the banks and triggered repeated SARs to FinCEN. None were filed by JPMorgan or its predecessor banks according to U.S. law enforcement until after Madoff turned himself in.

The brazenness of the activity was captured in a 2011 court complaint filed against JPMorgan by Irving Picard, the trustee of the Madoff victims’ fund. Picard told the court that “during 2002, Madoff initiated outgoing transactions to [Norman F.] Levy in the precise amount of $986,301 hundreds of times — 318 separate times, to be exact. These highly unusual transactions often occurred multiple times on a single day.

As another example, from December 2001 to March 2003, the total monthly dollar amounts coming into the 703 Account from Levy were almost always equal to the total monthly dollar amounts going out of the 703 Account to Levy.

There was no clear economic purpose for such repetitive transactions that had no net impact on Levy’s account at BLMIS [Bernard L. Madoff Investment Securities]. There was a huge spike in activity between Levy and the 703 Account in December 2001. In that month alone, Madoff engaged in approximately $6.8 billion worth of transactions with Levy…” (The term “703 Account” refers to Madoff’s primary business account at JPMorgan Chase which ended in the numbers “703.”)

Making JPMorgan’s failure to report even worse in U.S. law enforcement eyes was the fact that it did file a report of suspicious activity by Madoff with the United Kingdom’s Serious Organized Crime Agency (SOCA) on October 28, 2008 but failed to file the same report with U.S. authorities.

FinCEN’s Jennifer Shasky Calvery was particularly harsh in her assessment of JPMorgan’s failure to file a SAR at the press conference on January 7, where JPMorgan was charged with two felony counts, given a deferred prosecution agreement that puts the bank on probation for two years, and a $1.7 billion fine payable to the U.S. Department of Justice that will be distributed to Madoff’s victims. (Including the payment to the Justice Department and other Federal regulators and civil litigants, JPMorgan paid a total of $2.6 billion in the Madoff matter.)

Calvery said: “…it’s about lost opportunities and the catastrophic consequences that can flow. When JPMorgan failed to file a SAR with FinCEN, an opportunity to stop this fraud was missed. JPMorgan’s concerns about potential fraud went unheard, leaving law enforcement and regulators in the dark.”

Calvery is no Johnny come lately. She has served as Director of FinCEN since September 23, 2012. Prior to that she had a 15-year career at the U.S. Department of Justice where her focus was on money laundering and organized crime.

The takeaway from this press conference was clearly that the biggest crime committed by JPMorgan was its failure to file the SAR, thus aiding the “catastrophic consequences” that continued against Madoff’s victims. But what if another bank had filed a SAR in the matter with FinCEN and Federal law enforcement did nothing. What if Federal law enforcement or FinCEN is equally responsible for the “catastrophic consequences” that have destroyed the lives of Madoff victims throughout the U.S. and around the globe?

Within the documents filed against JPMorgan on January 7 by the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Southern District of New York, we learn that in the 1990s another bank where Madoff held an account observed these round-trip transactions between Madoff and Levy and filed a SAR with FinCEN.

According to the U.S. Attorney’s documents, Madoff was writing checks from an account at “Madoff Bank 2” – a bank other than JPMorgan – to Levy, a mutual customer of both Madoff’s firm and JPMorgan. Later the same day, Madoff would transfer money from his primary business account at JPMorgan to his account at Madoff Bank 2 to cover the earlier check. In the final leg of the transaction, Levy would transfer funds from his own JPMorgan Chase account to Madoff’s primary business account at JPMorgan in an amount sufficient to cover Madoff’s original check to him.

Levy is not mentioned by name in these documents but it’s clear from Picard’s earlier filing that the client involved is Levy. The documents also mention in a footnote that this client died in September 2005, the date of Levy’s death at age 93. Levy was a Manhattan real estate broker and one of Madoff’s largest and oldest clients.

According to the documents, Bank 2 investigated these round-trip transactions, met with Madoff employees, and concluded there was “no legitimate business purpose for these transactions, which appeared to be a ‘check kiting’ scheme.” Bank 2 terminated its relationship with Madoff Securities and filed its SAR with FinCEN, along with details about the facilitating actions of Levy and JPMorgan Chase’s predecessor bank, Chase Manhattan.

If the SAR was filed in the 90s, Wall Street On Parade wondered why a Federal investigation had not exposed Madoff at that time when the funds he ultimately stole from investors would have been significantly less. We filed a Freedom of Information Act request with FinCEN. A stunning response came back on January 20 of this year: there are no documents suggesting an investigation ever resulted from the 1990s SAR. (See FinCEN Response to FOIA from Wall Street On Parade in JPMorgan-Madoff Matter.)

Amanda Michanczyk, a Disclosure Officer at FinCEN wrote: “…we conducted a thorough search of our investigative and enforcement records for the time period estimated in your request using search terms you provided and can find no documents responsive to your request.”

This is what is called the “Wow Factor.” The Feds slap a $1.7 billion penalty on a bank, file a two-felony count indictment against it, put it on probation for two years – all for not filing a Suspicious Activity Report and yet when a bank did file a Suspicious Activity Report no documents exist to show there was ever an investigation. Welcome to the Orwellian juncture of high finance and Federal regulators. We are left to ponder if the investigative documents have been shredded, stolen, or no investigation ever occurred.

Last week, David Rosenfeld of the law firm Robbins Geller Rudman & Dowd LLP filed a lawsuit on behalf of the Central Laborers’ Pension Fund and Steamfitters Local 449 Pension Fund against 13 current and former executives of JPMorgan and its Board of Directors, including Chairman and CEO Jamie Dimon. The lawsuit charges these individuals with “recklessly permitting the Company to facilitate and perpetuate Madoff’s massive Ponzi scheme in the face of repeated and glaring warnings signs, and willfully failing to establish an adequate AML [anti-money-laundering] program.”

The lawsuit calls attention to what the Justice Department did not tell the public when it settled the case against JPMorgan: “The Statement of Facts depict a bank with unparalleled insight into Madoff’s fraud. However, the extent to which JPMorgan’s actual knowledge of or willful blindness to Madoff’s fraud reached the highest echelon of the Bank is not disclosed in the Deferred Prosecution Agreement, nor anywhere else in the public record.”

Anyone who has ever worked as a relationship manager or a stock broker at a major Wall Street bank knows that there is only one way that flagrant signs of money laundering are ignored over decades. Someone in a position of power had to shut down the automated warning system on this account and/or quash any internal investigations.

The fact that when FinCEN received a SAR from another major bank it still did not investigate or someone has erased the details of that investigation raises the additional alarm that someone in a position of power may have influenced that investigation inappropriately.

The Justice Department’s role in potentially preventing a full public accounting of the Madoff fraud was further called into question in December when news broke that the Justice Department had killed a subpoena request for internal JPMorgan documents related to the Madoff fraud that had been made by its primary bank regulator, the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency and supported by a second demand from the Inspector General of the U.S. Treasury.

Why the Justice Department would block regulators from obtaining critical documents, why FinCEN has no documents pertaining to the 1990s SAR filing, why brazen round-trip money laundering was allowed to continue at a major Wall Street bank are all issues waiting for transparent answers.

Suicides galore? Or murder run amok? If only Jethro and Tony were available to run this down.

Another Sudden Death of JPMorgan Worker: 34-Year Old Jason Alan Salais

By Pam Martens and Russ Martens: February 23, 2014

On the evening of Sunday, December 15 of last year, six weeks before the onset of the latest rash of tragic deaths of young men in their 30s employed at JPMorgan, the Pearland, Texas police received a call of a person in distress outside a Walgreens pharmacy at 6122 Broadway in Pearland. The individual in distress was Jason Alan Salais, a 34-year old Information Technology specialist who had worked at JPMorgan Chase since May 2008.

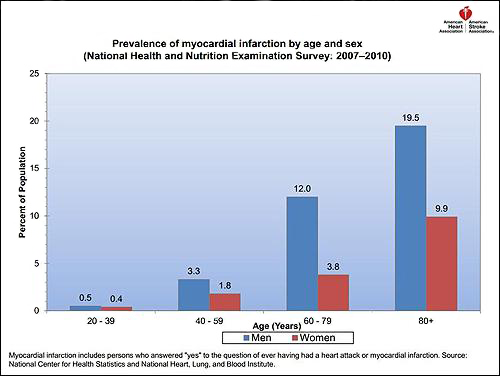

A family member confirmed to Wall Street On Parade that Salais died of a heart attack on the same evening the report of distress went in to the police. The incidence of heart attack or myocardial infarction among men aged 20 to 39 is one half of one percent of the population, according to the National Center for Health Statistics and National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, based on 2007 to 2010 data, marking this as another unusual death at JPMorgan.

A person identifying himself as Dave Steiner wrote the following about Salais in the online condolence book provided by the funeral home: “My condolences to your entire family at the sudden passing of Jason. When I had the pleasure of interviewing Jason to be a part of the team at J.P. Morgan back in 2008, it was clear to me within just a few short minutes that he was a man of character, intelligence, work ethic, kindness and integrity. In the years that followed, and until the sad news of this week, I was witness to his hard work, the friendships he built, stories of his beloved family and of course baseball…”

According to the LinkedIn profile for Salais, he was engaged in Client Technology Service “L3 Operate Support” and previously “FXO Operate L2 Support” at JPMorgan. Prior to joining JPMorgan in 2008, Salais had worked as a Client Software Technician at SunGard and a UNIX Systems Analyst at Logix Communications.

Six weeks after the sudden death of Salais, Gabriel Magee, a 39-year old Vice President who was also engaged in Information Technology at JPMorgan, this time in London, died under extremely suspicious circumstances. A Coroner’s Inquest into the matter will be held on May 15 in London.

Family and friends report that Magee was a happy, healthy, vibrant young man who emailed his girlfriend on the evening of January 27 to say he was finishing up at work and would be home shortly. When he did not arrive, his girlfriend notified police and called local hospitals. According to the Metropolitan Police in London, at around 8:02 a.m. the next morning, workers looking out their windows saw Magee’s body lying on a 9th level rooftop that jutted out from the 33-story JPMorgan building in the Canary Wharf section of London.

London newspapers immediately called the death a suicide, initially suggesting that thousands of commuters had seen Magee jump from the 33rd level rooftop. When Wall Street On Parade pressed the Metropolitan Police on the issue of actual eyewitnesses who had seen Magee jump, the Police backed away from the suggestion that the fall had actually been observed by eyewitnesses.

Magee worked in the European headquarters for JPMorgan at 25 Bank Street in the borough of Tower Hamlets. Drawings and plans submitted by JPMorgan to the borough after it purchased the building for £495 million in 2010, show that the 9th floor roof is accessible “via the stair from level 8 within the existing Level 9 plant enclosure…”

According to Magee’s LinkedIn profile, his specific area of specialty at JPMorgan was “Technical architecture oversight for planning, development, and operation of systems for fixed income securities and interest rate derivatives.”

Two young employees engaged in computer technology dying in such a short span of time might seem bizarre at a bank. But JPMorgan is not just any bank when it comes to computer technology. According to Anish Bhimani, the Chief Information Risk Officer at JPMorgan Chase, in an interview published at the Information Networking Institute (INI) at Carnegie Mellon, JPMorgan has “more software developers than Google, and more technologists than Microsoft…we get to build things at scale that have never been done before.”

Let that sink in for a moment: a bank that has “more software developers than Google.” The growing concern in Congress is that America’s biggest bank by assets is now so complex in terms of derivative risks on and off its books and software programs that are incomprehensible to its regulators, that it could pose systemic risk to the U.S. economy in a replay of the Citigroup debacle of 2008.

Six days after the death of Magee, Ryan Crane, an Executive Director involved in trading at JPMorgan’s New York office, was found dead in his home in Stamford, Connecticut on February 3. No cause of death or circumstances surrounding the death has been released to the public. The Chief Medical Examiner’s office will only say that the cause of death is “pending” and final results will not be announced for several more weeks.

Wall Street On Parade called the Stamford Police last week to ask for the police incident report. Under Connecticut sunshine laws that report should be available to the press. We were informed that if we were able to obtain the incident report, most information would likely be redacted.

Crane’s death on February 3 was not reported by any major media until February 13, ten days later, when Bloomberg News ran a brief story.

On February 18 of last week, again reports emerged of many witnesses having seen a 33-year old JPMorgan employee jump from the rooftop of a 30-story office building, Chater House, in Hong Kong where JPMorgan leases space. No eyewitnesses have been identified by name.

The decedent’s age and the fact he was employed by JPMorgan is all that the media can agree on. The South China Morning Post, an English language newspaper in Hong Kong, has published four articles calling the deceased an “investment banker” and warning that stress in this job may lead to suicide.

The South China Morning Post’s competitor in Hong Kong, The Standard, also an English language newspaper, reports that the employee is an accountant working in the finance department at JPMorgan – about as far removed from an investment banker as one could get.

The man’s name has been reported by various media in all of the following incarnations: Dennis Li, Li Junjie, Dennis Li Jun Jie, and Dennis Lee.

Despite four emails to Joe Evangelisti, a Managing Director and spokesperson for JPMorgan, Evangelisti would not provide the name and job title for the deceased employee, saying only that “Our HK team communicated with reporters late last week on this. Here’s the Bloomberg story.” The Bloomberg story provided by Evangelisti was seven sentences long and does not appear on the U.S. web site of Bloomberg News. The earlier story by Bloomberg News, circulated further at the San Francisco Chronicle, depicted the employee as a “foreign exchange trader” citing the (wait for it) South China Morning Post.

When Wall Street On Parade pointed out via email to Evangelisti that under Fair Disclosure rules (Reg FD) a publicly traded company in the U.S. has an obligation to issue its press releases to everyone at the same time and that we would like a direct statement from him on the employee’s name and job title (not another media outlet’s interpretation of JPMorgan’s statement), Wall Street On Parade heard no further from Evangelisti, despite openly copying the media relations folks at the Securities and Exchange Commission on the entire email thread.

The New York Post pointed out in its reporting that there is “no other known link between any of the deaths” outside of the individuals working for the same company. In fact, there are numerous links: all of the men are in their 30s, while according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the expected longevity in 2011 for a U.S. male is 76.3 years.

All of the men are believed to have been covered by a life insurance policy which pays JPMorgan upon the death of its employees. (Insurance experts say that larger death benefits can be obtained on younger, highly skilled workers because the death benefit is a function of the number of years of lost earnings.)

But perhaps the most important link is this: three weeks before the death of Salais and within a little more than a month of the other deaths, JPMorgan had been put under a form of probation by the U.S. Justice Department.

In exchange for a Deferred Prosecution Agreement that ran for two years and $1.7 billion in fines to avoid the criminal indictment of individuals and the firm for facilitating the largest financial fraud in U.S. history, Bernard Madoff’s Ponzi scheme, JPMorgan was forced to agree to “secure the attendance and truthful statements or testimony of any past or current officers, agents, or employees at any meeting or interview or before the grand jury … provide in a responsive and prompt fashion, and upon request, on an expedited schedule, all documents, records, information and other evidence in JPMorgan’s possession, custody or control as may be requested by the Office, the FBI, or designated governmental agency … bring to the Office’s attention all criminal conduct by JPMorgan or any of its employees … commit no crimes under the federal laws of the United States subsequent to the execution of this Agreement.”

When a rash of sudden deaths occur among a most unlikely cohort of 30-year olds at a bank that has just settled felony charges and been put on notice that it will be indicted if it commits any further felonies; when it is currently under investigation on multiple continents for potentially committing criminal acts in the realm of interest rate and/or foreign exchange rigging — for the press to cavalierly call these deaths “non suspicious” before inquests have been conducted and findings released by medical examiners shows an unseemly indifference to a worker’s life and an alarming insensitivity to the grief stricken families still searching for answers.

At least one reporter was on top of this death spectre.

We hope not under it.

A Rash of Deaths and a Missing Reporter – With Ties to Wall Street Investigations

By Pam Martens: February 3, 2014

Senator Carl Levin's Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations Is Probing Global Banks' Involvement in the U.S. Commodities Markets

In a span of four days last week, two current executives and one recently retired top ranking executive of major financial firms were found dead. Both media and police have been quick to label the deaths as likely suicides. Missing from the reports is the salient fact that all three of the financial firms the executives worked for are under investigation for potentially serious financial fraud.

The deaths began on Sunday, January 26. London police reported that William Broeksmit, a top executive at Deutsche Bank who had retired in 2013, had been found hanged in his home in the South Kensington section of London. The day after Broeksmit was pronounced dead, Eric Ben-Artzi, a former risk analyst turned whistleblower at Deutsche Bank, was scheduled to speak at Auburn University in Alabama on his allegations that Deutsche had hid $12 billion in losses during the financial crisis with the knowledge of senior executives. Two other whistleblowers have brought similar charges against Deutsche Bank.

Deutsche Bank is also under investigation by global regulators for potentially rigging the foreign exchange markets – an action similar to the charges it settled in 2013 over its traders’ involvement in the rigging of the interest rate benchmark, Libor.

Just two days after Broeksmit’s death, on Tuesday, January 28, a 39-year old American, Gabriel Magee, a Vice President at JPMorgan in London, plunged to his death from the roof of the 33-story European headquarters of JPMorgan in Canary Wharf. According to Magee’s Linked-In profile, he was involved in “Technical architecture oversight for planning, development, and operation of systems for fixed income securities and interest rate derivatives.”

Magee’s parents, Bill and Nell Magee, are not buying the official story according to press reports and are planning to travel from the United States to London to get at the truth. One of their key issues, which should also trouble the police, is how an employee obtains access to the rooftop of one of the mostly highly secure buildings in London.

Nell Magee was quoted in the London Evening Standard saying her son was “a happy person who was happy with his life.” His friends are equally mystified, stating he was in a happy, long-term relationship with a girlfriend.

JPMorgan is under the same global investigation for potential involvement in rigging foreign exchange rates as is Deutsche Bank. The firm is also said to be under an investigation by the U.S. Senate’s Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations for its involvement in potential misconduct in physical commodities markets in the U.S. and London.

One day after Magee’s death, on Wednesday, January 29, 2014, 50-year old Michael (Mike) Dueker, the Chief Economist at Russell Investments, is said to have died from a 50-foot fall from a highway ramp down an embankment in Washington state. Again, suicide is being presented by media as the likely cause. (Do people holding Ph.D.s really attempt suicide by jumping 50 feet?)

According to Dueker’s official bio, prior to joining Russell Investments, he was an assistant vice president and research economist at the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis from 1991 to 2008. His duties there included serving as an associate editor of the Journal of Business and Economic Statistics. He also was editor of Monetary Trends, a monthly publication of the St. Louis Fed.

Bloomberg News quotes William Poole, former President of the St. Louis Fed from 1998 to 2008, saying “Everyone respected his professional skills and good sense.”

According to a report in the New York Times in November of last year, Russell Investments was one of a number of firms that received subpoenas from New York State regulators who are probing the potential for pay-to-play schemes involving pension funds based in New York. No allegations of wrongdoing have been made against Russell Investments in the matter.

The case of David Bird, the oil markets reporter who had worked at the Wall Street Journal for 20 years and vanished without a trace on the afternoon of January 11, has this in common with the other three tragedies: his work involves a commodities market – oil – which is under investigation by the U.S. Senate’s Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations for possible manipulation. The FBI is involved in the Bird investigation.

Bird left his Long Hill, New Jersey home on that Saturday, telling his wife he was going for a walk. An intentional disappearance is incompatible with the fact that he left the house wearing a bright red jacket and without his life-sustaining medicine he was required to take daily as a result of a liver transplant. Despite a continuous search since his disappearance by hundreds of volunteers, local law enforcement and the FBI, Bird has not been located.

When a series of tragic events involving one industry occur within an 18-day timeframe, the statistical probability of these events being random is remote. According to a number of media reports, JPMorgan is conducting an internal investigation of the death of Gabriel Magee. Given that JPMorgan, Deutsche Bank and Russell Investments are subjects themselves of investigations, a more serious, independent look at these deaths is called for.

Update: See related article: Suspicious Death of JPMorgan Vice President, Gabriel Magee, Under Investigation in London

As I've mentioned before, the death of this "jumper" is more than suspect.

JPMorgan Vice President’s Death in London Shines a Light on the Bank’s Close Ties to the CIA

By Pam Martens and Russ Martens: February 12, 2014

The nonstop crime news swirling around JPMorgan Chase for a solid 18 months has started to feel a little spooky – they do lots of crime but never any time; and with each closed case, a trail of unanswered questions remains in the public’s mind.

Just last month, JPMorgan Chase acknowledged that it facilitated the largest Ponzi scheme in history, looking the other way as Bernie Madoff brazenly turned his business bank account at JPMorgan Chase into an unprecedented money laundering operation that would have set off bells, whistles and sirens at any other bank.

The U.S. Justice Department allowed JPMorgan to pay $1.7 billion and sign a deferred prosecution agreement, meaning no one goes to jail at JPMorgan — again. The largest question that no one can or will answer is how the compliance, legal and anti-money laundering personnel at JPMorgan ignored for years hundreds of transfers and billions of dollars in round trip maneuvers between Madoff and the account of Norman Levy. Even one such maneuver should set off an investigation. (Levy is now deceased and the Trustee for Madoff’s victims has settled with his estate.)

Then there was the report done by the U.S. Senate’s Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations of the London Whale episode which left the public in the dark about just what JPMorgan was doing with stock trading in its Chief Investment Office in London, redacting all information in the 300-page report that related to that topic.

Wall Street On Parade has been filing Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests with the Federal government in these matters, and despite the pledge from our President to set a new era of transparency, thus far we have had few answers coming our way.

<One reason that JPMorgan may have such a spooky feel is that it has aligned itself in no small way with real-life spooks, the CIA kind.

Just when the public was numbing itself to the endless stream of financial malfeasance which cost JPMorgan over $30 billion in fines and settlements in just the past 13 months, we learned on January 28 of this year that a happy, healthy 39-year old technology Vice President, Gabriel Magee, was found dead on a 9th level rooftop of the bank’s 33-story European headquarters building in the Canary Wharf section of London.

The way the news of this tragic and sudden death was stage-managed by highly skilled but invisible hands, turning a demonstrably suspicious incident into a cut-and-dried suicide leap from the rooftop (devoid of eyewitnesses or motivation) had all the hallmarks of a sophisticated covert operation or coverup.

The London Evening Standard newspaper reported the same day that “A man plunged to his death from a Canary Wharf tower in front of thousands of horrified commuters today.” Who gave that completely fabricated story to the press? Commuters on the street had no view of the body because it was 9 floors up on a rooftop – a rooftop that is accessible from a stairwell inside the building, not just via a fall from the roof. Adding to the suspicions, Magee had emailed his girlfriend the evening before telling her he was finishing up and would be home shortly.

If JPMorgan’s CEO, Jamie Dimon, needed a little crisis management help from operatives, he has no shortage of people to call upon. Thomas Higgins was, until a few months ago, a Managing Director and Global Head of Operational Control for JPMorgan. (A BusinessWeek profile shows Higgins still employed at JPMorgan while the New York Post reported that he left late last year.) What is not in question is that Higgins was previously the Senior Officer and Station Chief in the CIA’s National Clandestine Service, a component of which is the National Resources Division. (Higgins’ bio is printed in past brochures of the CIA Officers Memorial Foundation, where Higgins is listed with his JPMorgan job title, former CIA job title, and as a member of the Foundation’s Board of Directors for 2013.)

According to Jeff Stein, writing in Newsweek on November 14, the National Resources Division (NR) is the “biggest little CIA shop you’ve never heard of.” One good reason you’ve never heard of it until now is that the New York Times was asked not to name it in 2001. James Risen writes in a New York Times piece: [the CIA’s] “New York station was behind the false front of another federal organization, which intelligence officials requested that The Times not identify. The station was, among other things, a base of operations to spy on and recruit foreign diplomats stationed at the United Nations, while debriefing selected American business executives and others willing to talk to the C.I.A. after returning from overseas.”

Stein gets much of that out in the open in his piece for Newsweek, citing sources who say that “its intimate relations with top U.S. corporate executives willing to have their companies fronting for the CIA invites trouble at home and abroad.” Stein goes on to say that NR operatives “cultivate their own sources on Wall Street, especially looking for help keeping track of foreign money sloshing around in the global financial system, while recruiting companies to provide cover for CIA operations abroad. And once they’ve seen how the other 1 percent lives, CIA operatives, some say, are tempted to go over to the other side.”

We now know that it was not only the Securities and Exchange Commission, the U.S. Treasury Department’s FinCEN, and bank examiners from the Comptroller of the Currency who missed the Madoff fraud, it was top snoops at the CIA in the very city where Madoff was headquartered.

Stein gives us even less reason to feel confident about this situation, writing that the NR “knows some titans of finance are not above being romanced. Most love hanging out with the agency’s top spies — James Bond and all that — and being solicited for their views on everything from the street’s latest tricks to their meetings with, say, China’s finance minister.

JPMorgan Chase’s Jamie Dimon and Goldman Sach’s Lloyd Blankfein, one former CIA executive recalls, loved to get visitors from Langley. And the CIA loves them back, not just for their patriotic cooperation with the spy agency, sources say, but for the influence they have on Capitol Hill, where the intelligence budgets are hashed out.”

Higgins is not the only former CIA operative to work at JPMorgan. According to a LinkedIn profile, Bud Cato, a Regional Security Manager for JPMorgan Chase, worked for the CIA in foreign clandestine operations from 1982 to 1995; then went to work for The Coca-Cola Company until 2001; then back to the CIA as an Operations Officer in Afghanistan, Iraq and other Middle East countries until he joined JPMorgan in 2011.

In addition to Higgins and Cato, JPMorgan has a large roster of former Secret Service, former FBI and former law enforcement personnel employed in security jobs. And, as we have reported repeatedly, it still shares a space with the NYPD in a massive surveillance operation in lower Manhattan which has been dubbed the Lower Manhattan Security Coordination Center.

JPMorgan and Jamie Dimon have received a great deal of press attention for the whopping $4.6 million that JPMorgan donated to the New York City Police Foundation. Leonard Levitt, of NYPD Confidential, wrote in 2011 that New York City Police Commissioner Ray Kelly “has amended his financial disclosure forms after this column revealed last October that the Police Foundation had paid his dues and meals at the Harvard Club for the past eight years. Kelly now acknowledges he spent $30,000 at the Harvard Club between 2006 and 2009, according to the Daily News.”

JPMorgan is also listed as one of the largest donors to a nonprofit Foundation that provides college tuition assistance to the children of fallen CIA operatives, the CIA Officers Memorial Foundation. The Foundation also notes in a November 2013 publication, the Compass, that it has enjoyed the fundraising support of Maurice (Hank) Greenberg. According to the publication, Greenberg “sponsored a fundraiser on our behalf. His guest list included the who’s who of the financial services industry in New York, and they gave generously.”

Hank Greenberg is the former Chairman and CEO of AIG which collapsed into the arms of the U.S. taxpayer, requiring a $182 billion bailout. In 2006, AIG paid $1.64 billion to settle federal and state probes into fraudulent activities. In 2010, the company settled a shareholders’ lawsuit for $725 million that accused it of accounting fraud and stock price manipulation. In 2009, Greenberg settled SEC fraud charges against him related to AIG for $15 million.

Before the death of Gabriel Magee, the public had lost trust in the Justice Department and Wall Street regulators to bring these financial firms to justice for an unending spree of fleecing the public. Now there is a young man’s unexplained death at JPMorgan. This is no longer about money. This is about a heartbroken family that will never be the same again; who can never find peace or closure until credible and documented facts are put before them by independent, credible law enforcement.

The London Coroner’s office will hold a formal inquest into the death of Gabriel Magee on May 15. Wall Street On Parade has asked that the inquest be available on a live webcast as well as an archived webcast so that the American public can observe for itself if this matter has been given the kind of serious investigation it deserves. We ask other media outlets who were initially misled about the facts in this case to do the same.

I couldn't believe the term "death derivatives."

What a telling use of verbiage.

As Bank Deaths Continue to Shock, Documents Reveal JPMorgan Has Been Patenting Death Derivatives

By Pam Martens and Russ Martens: February 17, 2014

The probability of two vibrant young men in their 30s who are employed by the same global bank but separated by an ocean dying within six days of each other is remote. And few companies are in as good a position to understand just how remote as is JPMorgan: since 2010, it has received four patents on quantifying longevity risks and structuring wagers via death derivatives.

The two deaths at JPMorgan remain unexplained. Gabriel Magee, a 39-year old technology Vice President was found dead on the 9th level rooftop of JPMorgan’s European headquarters at 25 Bank Street in the Canary Wharf section of London on January 28 of this year. A London coroner’s inquest is scheduled for May 15 to determine the cause of death. Six days later, Ryan Crane, a 37-year old Executive Director involved in trading at JPMorgan’s New York office was found dead at his Stamford, Connecticut home. Wall Street On Parade spoke with the Chief Medical Examiner’s office in Connecticut and was told the cause of death is “pending,” with final results expected in a few weeks.

Magee’s death was originally reported by London newspapers as a jump from the 33rd level rooftop of JPMorgan’s building with the strong implication that eyewitnesses had observed the jump. The London Evening Standard tweeted: “Bankers watch JP Morgan IT exec fall to his death from roof of London HQ,” which then linked to their article which said in its opening sentence that “A man plunged to his death from a Canary Wharf tower in front of thousands of horrified commuters today.”

When Wall Street On Parade contacted the Metropolitan Police in London a few days later, there was no assurance that even one eyewitness was on record as having seen Magee jump from the building.

Crane’s death is equally problematic. The death occurred on February 3 but the first major media to report it was Bloomberg News on February 13, ten days after the fact, and making no mention of Magee’s unexplained death just six days prior.

According to information available at the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office, JPMorgan created the LifeMetrics Index in March 2007 as an “international index designed to benchmark and trade longevity risk.” The index was said to enable pension plans to hedge the risk of payments to retirees and incorporated “historical and current statistics on mortality rates and life expectancy, across genders, ages, and nationalities.” From 2010 through 2013, JPMorgan has received patent approval on four longevity related patents.

Reuters reported on August 26, 2013 that the long-term longevity bets taken on by the big banks have now started to cause pain as international capital rules known as Basel III require more capital to be set aside for longer-dated positions. The article noted that “JPMorgan likely has the biggest holdings of long-dated swaps because it is the biggest swaps trader on Wall Street, responsible for about 30 percent of the market by some measures, traders at rival firms said.”

One extremely long longevity bet taken on by JPMorgan was reported by Insurance Risk on October 1, 2008. According to the publication, JPMorgan entered into a 40-year £500 million notional longevity swap with Canada Life whereby Canada Life would make a fixed annual payment in return for a floating liability-matching payment that would increase if the annuitants lived longer than expected. JPMorgan was believed to have passed on some of the risk to hedge fund investors but retained the counterparty risk. Because many of these deals are private, the full extent of JPMorgan’s exposure in this area is not known.

Wall Street veterans have also commented on the fact that JPMorgan may actually stand to profit from the early deaths of the two young men in their 30s.

As we reported in March of last year, when the U.S. Senate’s Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations released its report on JPMorgan’s high risk bets known as the London Whale debacle, its Exhibit 81 showed that JPMorgan’s Chief Investment Office was also overseeing Bank Owned Life Insurance (BOLI) and Corporate Owned Life Insurance (COLI) plans which allow the corporation to reap huge tax benefits by taking out life insurance policies on workers – even low wage workers – and naming the corporation the beneficiary of the death benefit. Both the buildup in the policy and the benefit at death are received tax free to the corporation.

According to the exhibit, the Chief Investment Office was tasked with “Maximization of tax-advantaged investments of life insurance premiums” for the BOLI/COLI plans. According to a report in the Wall Street Journal in 2009, JPMorgan had $12 billion in BOLI, noting that a JPMorgan spokesperson had confirmed the figure. Other insurance industry experts put the total for both BOLI and COLI at JPMorgan significantly higher.

In September of last year, Risk Magazine reported that the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, the International Organization of Securities Commissions and the International Association of Insurance Supervisors had published a report in August warning regulators that longevity swaps may expose banks to longevity tail risk – meaning, for example, that actual death rates in a given portfolio may vary dramatically from a large population index.

One advisor is quoted as follows in the article: “You can see from the position paper that this market has a lot of characteristics that regulators don’t like in terms of banks getting involved in it. It’s based on long-dated risks, upfront payments and a serious element of hubris in assuming that the banks can model these risks better than the people who originated them. It’s potentially a market big enough to cause serious problems if it caught on and went wrong.”

That things are starting to go seriously wrong was evident in a Bloomberg News report that emerged last Friday. AIG reported that it was taking a $971 million impairment charge before taxes for 2013 on its holdings of life settlement contracts because people were living longer than expected. AIG is the company that was bailed out by the U.S. taxpayer to the tune of $182 billion during the financial crisis because of bets gone wrong.

Related Article:

A Rash of Deaths and a Missing Reporter — With Ties to Wall Street Investigations

If anyone hasn't figured by now that everyone (and I mean everyone) in government and banking weren't aware of how Madoff was funneling funds for the benefit of someone very powerful with these spurious trades, I hope they never work again in a position requiring intelligence.

JPMorgan and Madoff Were Facilitating Nesting Dolls-Style Frauds Within Frauds

By Pam Martens: January 13, 2014

Last week JPMorgan Chase paid $2.6 billion in fines and restitution, signed a deferred prosecution agreement and walked away from their 22-year involvement with Bernie Madoff’s Ponzi scheme. But according to court documents filed in 2011 by the Trustee of the Madoff victims’ fund, Irving Picard, this was not a simple case of poor risk management at JPMorgan. This was an operation structured like those Russian nesting dolls, with the Ponzi scheme as the outside doll with many more frauds layered inside the big one.

After reading the documents released by the Justice Department in connection with the settlement, the Los Angeles Times asked in a photo caption of a smirking Madoff outside of Federal Court: “Bernie Madoff: Was he part of the JPMorgan ring, or was JPMorgan part of his ring?”

The New York Times had a far more charitable stance, with Floyd Norris writing: “Did JPMorgan Chase deliberately cover up Bernard L. Madoff’s fraud? The documents released this week by federal prosecutors do not show it did, and I suspect it did not.”

Interestingly, the folks in sunny California, 2400 miles away from Wall Street, had an epiphanous moment in that photo caption while the Times assumed an all too common ostrich position when it comes to Wall Street.

According to the Securities Investor Protection Corporation (SIPC), the Justice Department prosecutors who settled the case against JPMorgan Chase used the investigative material from Picard to bring their charges and settle the case. Those court filings show layers upon layers of frauds within the Ponzi scheme.

For starters, JPMorgan Chase used unaudited financial statements and skipped the required steps of bank due diligence to make $145 million in loans to Madoff’s business, according to Picard. Lawyers for the Trustee write that from November 2005 through January 18, 2006, JPMorgan Chase loaned $145 million to Madoff’s business at a time when the bank was on “notice of fraudulent activity” in Madoff’s business account and when, in fact, Madoff’s business was insolvent.

The reason for the JPMorgan Chase loans was because Madoff’s business account, referred to as the 703 account, was “reaching dangerously low levels of liquidity, and the Ponzi scheme was at risk of collapsing.” JPMorgan, in fact, “provided liquidity to continue the Ponzi scheme,” according to Picard.

Clearly, this is fraud number two on the part of someone – loan fraud.

Fraud number three occurred when JPMorgan Chase and its predecessor banks extended tens of millions of dollars in loans to Norman F. Levy and his family so they could invest with the insolvent Madoff. (Levy died in 2005 at age 93 without being charged with any crimes. Levy’s accountant, Paul J. Konigsberg, was indicted in September of last year and charged by the Securities and Exchange Commission in a civil action. Konigsberg has pleaded not guilty in both cases.)

According to Picard, Levy had $188 million in outstanding loans in 1996, which he used to funnel money into Madoff investments. Picard’s lawyers told the court that JPMorgan Chase (JPMC) “referred to these investments as ‘special deals.’ Indeed, these deals were special for all involved: (a) Levy enjoyed Madoff’s inflated return rates of up to 40% on the money he invested with Madoff; (b) Madoff enjoyed the benefits of large amounts of cash to perpetuate his fraud without being subject to JPMC’s due diligence processes; and (c) JPMC earned fees on the loan amounts and watched the ‘special deals’ from afar, escaping responsibility for any due diligence on Madoff’s operation.”

A critical piece of evidence against JPMorgan was that despite funneling loans to both Madoff and Levy, the bank “advised the rest of its Private Bank customers not to invest with Madoff,” according to Picard.

On paper, according to Picard, Levy was worth $1.5 billion in 1998. He was such an important customer to JPMorgan and its predecessor firms that he was given his own office at the bank – a situation that perhaps fueled the Los Angeles Times’ question of just who was a part of whose gang.

Levy was a commercial real estate broker and, according to an article by Mark Seal in the April 2009 issue of Vanity Fair, at one point Levy “had an ownership stake in 70 properties, including the Seagram Building and 21 shopping centers across America…” There is some basis for suspicion that inflated and fraudulent account statements provided by either JPMorgan Chase and/or Madoff may have been used to obtain real estate loans. If so, that would constitute yet another fraud.

According to Picard, Levy’s relationship with JPMorgan’s predecessor banks predated his relationship with Madoff by 31 years. Once Levy was a Madoff client, the relationship included classic, unchecked evidence of money laundering for years and years that should have resulted in legally-mandated Suspicious Activity Reports (SARs) filed with the U.S. Treasury Department’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN). Even after another bank detected the activity in the late 90s and reported the transactions to FinCEN, JPMorgan Chase and its predecessor banks failed to file their own mandated SARs and not only allowed the activity to continue but allowed it to increase dramatically in dollar terms.

Having worked on Wall Street myself for 21 years, I can assure you that just one atypical transfer of a large sum of money between accounts will elicit a serious investigation by an honest Wall Street firm’s compliance department. It will drill down until it gets proof that the transfer had a legitimate basis.

What was happening in Madoff’s account was so over the top that it is virtually impossible to reconcile it with a legitimate compliance department unless some higher up simply shut down the normal bank controls. Picard told the court that “during 2002, Madoff initiated outgoing transactions to Levy in the precise amount of $986,301 hundreds of times — 318 separate times, to be exact. These highly unusual transactions often occurred multiple times on a single day.”

Levy’s accountant, Konigsberg, is charged with routinely telling a Madoff employee to regenerate statements for the clients referred to him by Madoff, dictating the terms of what kind of profits and losses he wanted to see on the statements each year.

The SEC says in its complaint that Konigsberg “was compensated for his work in connection with these BMIS [Bernard Madoff Investment Securities] clients. He received fees directly for the accounting services that he provided to these clients, and additionally, BMIS and Bernard Madoff (Madoff) compensated Konigsberg with a monthly fee of $15,000 or $20,000 as a ‘retainer’ for providing accounting services to a wealthy and longtime Madoff client and his adult children.”

The SEC cites one example where “Konigsberg instructed Employee X that his client was to experience no more than $18 million in losses. In giving these instructions, Konigsberg understood that Employee X and BMIS would create unlawful, backdated trades to benefit his clients.”

And here we have, at least, frauds number four and five. Tax fraud and the fraudulent creation of broker-dealer records. And we’ve barely scratched the surface thus far.

Like we said, think Matryoshka, the Russian Nesting Dolls’ frauds within frauds.

How many people/institutions does this make that tried to turn in Madoff over decades of criminality?

Anybody got a head count? (We've got a body count going already.)

Who Was the Mysterious ‘Bank 2’ That Turned In Madoff – To No Avail

By Pam Martens: January 9, 2014

According to the settlement documents released Tuesday by Preet Bharara, the U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of New York, Bernie Madoff was not content to simply engineer the largest Ponzi scheme under the very noses of the largest squad of regulators in the history of finance, he was simultaneously running a brazen check-kiting scheme under the same noses.

Irving Picard, the Trustee of the Madoff victims’ fund set up by the Securities Investor Protection Corporation (SIPC), provided a great amount of detail on this operation in a court filing against JPMorgan in 2011. This week, U.S. Attorney Bharara added additional details.

According to Bharara, Madoff was writing checks from an account at “Madoff Bank 2” – a bank other than JPMorgan – to Norman F. Levy, a mutual customer of both Madoff’s firm and JPMorgan. Later the same day, Madoff would transfer money from his primary business account at JPMorgan to his account at Madoff Bank 2 to cover the earlier check. In the final leg of the transaction, Levy would transfer funds from his own JPMorgan Chase account to Madoff’s primary business account at JPMorgan in an amount sufficient to cover Madoff’s original check to him.

Bharara does not mention Levy by name but it’s clear from Picard’s earlier filing that the client involved is Levy. Bharara also mentions in a footnote that this client died in September 2005, the date of Levy’s death at age 93. Levy was a Manhattan real estate broker and one of Madoff’s largest and oldest clients.

The Justice Department said “These round-trip transactions occurred on a virtually daily basis for a period of years, and were each in the amount of tens of millions of dollars. Because of the delay between when the transactions were credited and when they were cleared (referred to as the ‘float’), the effect of these transactions was to make Madoff’s balances . . . appear larger than they otherwise were, resulting in inflated interest payments to Madoff by JPMorgan Chase.”

Now comes the shocker: Bank 2 investigated these round-trip transactions, met with Madoff employees, and concluded there was “no legitimate business purpose for these transactions, which appeared to be a ‘check kiting’ scheme.” Bank 2 terminated its relationship with Madoff Securities and turned him in to the U.S. Treasury Department’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN), along with details about the facilitating actions of Levy and JPMorgan Chase’s predecessor bank, Chase Manhattan.

To turn in Madoff, Bank 2’s employees filed a Suspicious Activity Report (SAR) with FinCEN. This would leave any experienced employee of a Wall Street bank or brokerage firm trembling in panic.

The most famous case of check-kiting on the part of E.F. Hutton in the 1980s ended with the firm pleading guilty to 2,000 counts of mail and wire fraud and the end to the 80-year old storied firm.

But those JPMorgan folks are a tough bunch. According to Bharara, not only did the check-kiting continue but the dollar amounts increased, with the kiting occurring between accounts strictly within JPMorgan Chase. By December 2001, there was $6.8 billion in transactions in units of typically $90 million at a time. (What was really going on here has yet to be explained.)

Stephen Harbeck, the President of SIPC, may have inadvertently leaked the name of the mysterious Bank 2 in January 2011 when he responded to a series of questions in writing to Congressman Scott Garrett of New Jersey. According to Harbeck, there were only 11 banks where Madoff had established accounts which made transfers to and from the so-called “703” main Madoff business account at JPMorgan Chase or its predecessor banks. On that list, there is only one bank which stopped doing business with Madoff after a two year period — Bankers Trust. The letter also shows under the column titled “Purpose of Account,” that the Bankers Trust account was used to fund outflows to Madoff’s Investment Advisory clients.

We now know that in addition to multiple investigations by the Securities and Exchange Commission that went no where, the U.S. Treasury Department also failed to stop Madoff from defrauding customers for another decade.

3 comments:

Undoubtedly.

It's.

Coming.

I just hope it's not.

Nuclear.

wow

sooo much to read here

I will try to get through it

just wanted to tell you how I appreciate your hard work on this

it IS a huge story and you do it skillfully I am really impressed!!

Thanks, Peter,

It's all about getting the word out.

But I really appreciate your thoughtful comments.

Post a Comment